Making Indians, yet again

When India was made, no special need for making Indians was felt.

That should be somewhat surprising. There was this great aspiration of building a republican polity based on universal suffrage. The whole Indian freedom struggle was a long pedagogical project, led by Gandhi but also enthusiastically enjoined by leaders at various levels, of transforming the political imagination and creating new rules of engagement. 1947 was not just the realisation of that project, it was to be a beginning of a more comprehensive transformation of what it means to be an Indian.

As Independence unfolded, various leaders, Nehru and Ambedkar among them, stressed how this would require a new political imagination. There was the vast and ambitious project of the constitution, pulling the disparate communities together into the union. And, yet, precise little was said about what it means to be this new Indian; the debate was muted and deemed unnecessary. The educational enterprise that the new country would embark thereon emphasised building technological capacity of the nation - hence, the great project of building the IITs - but left unanswered the questions of identity, that of moral and the civic engagement. There was no project of 'national education' as an earlier generation of Indians, at the turn of the Twentieth Century, tried to embark on. There was limited enthusiasm to establish a new national curriculum, a conversation about values, what it means to be an Indian. Tilak's idea of 'a new religion - an Indian religion' - was by then utterly lost and fragmented 'by narrow domestic walls'. As India came to be, the Indian was taken for granted.

It's worth wondering why this was so. One may conclude that the identity of an Indian was taken to be pre-existing, forged through millennia and only now being awakened - hence, Nehru's poetic invocation of a long-awaited tryst at the midnight hour. But this itself was contingent on the politics of the moment: The creation of Pakistan reframed the Indian nationalist politics in an odd way. One, Indian politicians reconciled the terrible tragedy of the partition by positioning India as the original state - one that always existed and one Pakistan has left - built as a 'palimpsest' of cultures, religions and ideas, an accumulative civilisation. Two, at the same time and for the same logic, they rejected the idea of 'original Indian', primarily to deal with the potent threat of Hindu fundamentalism. For the founders at the time of India's founding, there was nothing new to be founded, just restored; India was not to be an utopian project of nation-making.

But, with hindsight, we may see that they were not operating in a vacuum. There were strong global forces shaping India at the same time. Rather than being an act of restoration, the foundation of India kept it as a successor state, limited by its recent history and colonial imagination. Besides, the colonialists were not going anywhere. The British empire, in the following decades, would melt away in a vast global pedagogic project of Anglo-America, which India would become a part of. A network of global institutions, a system of worth and of values, financial architecture, ways of education and what counts as knowledge, of art, literature, music and tastes, and more, will invade and seek to shape everyday lives and desires of Indians. The Yin-and-Yang of desire and disappointment at the mercy of the Anglo-American empire shaped the lives of Indians more than that of the Chinese or the Iranians, remaining as they are behind the protective veils of their language, education systems and values. It was different from that of the Japanese, who embraced the Western project intentionally and eclectically. Indians, instead, somewhat accepted their place in the global system of knowledge, gleefully surrendering to back-office work and becoming the world's 'manpower provider'. The language of the liberal empire, words such as 'middle class', 'demographic dividend', 'skills', became the discursive universe of the Indian nation-making.

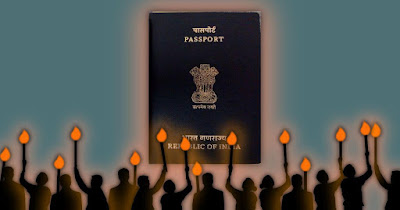

As the Anglo-American pedagogic project comes to its tired conclusion and the institutional framework of consensual western hegemony starts to break down, the question of making Indians confront us again. The illusion of democracy without civic education or engagement has now become weak and the comfortable backseat of the global supply chain has become contested. Too many people have been left out from the neo-liberal disneyland that India was building for two decades - suddenly they have emerged from their subterranean obscurity as a pandemic has broken out. In this season of breaking, a new-old project of finding the 'original Indian', in its Hindu past, has gotten underway.

However, India will need more. Revivalists would eventually find that India they imagined isn't there. They would come to know - perhaps they already know - the simultaneity of a timeless vision of India and one defined by post-partition hatred and conflict is difficult to sustain. Something has to give: Either they have to embrace something bigger than post-colonial Hinduism or they have to give up on the special place in the world that a democratic India claimed and earned for itself. But, out of their often-violent cultural revolution, would emerge the urgent imperative of making Indians once again.

Comments