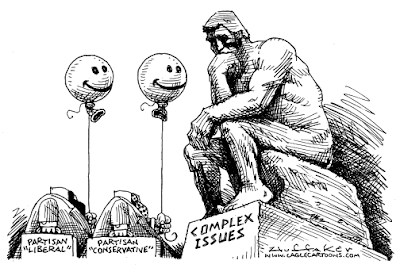

Should I call myself a conservative?

In this day and age when political labels are liberally applied and some impossible categories, such as left-liberal, it's really confusing where anyone stands.

Indeed, the wise opportunists of our age know the true value of these labels: Labels for them are keys to offices. The only other use of them is on opponents to undermine their arguments and question their integrity.

And, yet, when someone isn't being labelled, they are being asked. A middle-class education predicated on ideas of truth and integrity may still instil a sense of commitment to one idea or another; the quest for belonging may club one with fellow-travellers who still believed in belief.

So is indeed my predicament: It's hard for me to avoid some labels, given my ethnic origin and the particular time of my birth. Besides, my indulgence in reading widely and failure to strictly adhere to the cult of one or the other great men make me for any true believer category. Indeed, lumpers will put me in the Liberal basket, given that such intellectual promiscuity befits only the liberals, but my shaky faith in the voodoo of the market makes that a strenuous categorisation.

But if I am asked - and indeed, I am asked often - I say I am an Indian Conservative. I don't particularly like the 'conservative' label, of course. To start with, there is a nasty imperialist ring to it; and besides, in its modern usage, Conservatives are those true revolutionaries pushing the twin agenda of monetisation of everything and advancing a barely concealed Anglo-American imperialism. I am perhaps more Indian than Conservative, or an Indian-style conservative.

Because this isn't a usual category and can be defined neither who I vote for nor which dead thinker I worship, because I am an eclectic voter and I read Marx and Burke with the same enthusiasm. My claims of being a conservative rest on the way I see certain issues. Indeed, the Indian Conservative label has many claimants, particularly as India's ruling dispensation runs their regime with a traditionalist garb; the other side, the opposition in India, is led by a party which treats Indian voters as children in the need of paterfamilias and keeps a family in control. But I argue that conservatism is neither about radical traditionalism nor servile pseudo-monarchism, but rather a way of understanding the world around communities, culture and individual's place in it.

So, here is my Conservative Test, five interrogative perspectives of seeing the world that make me act in the way I do.

First, I believe that society is a complex mechanism made of overlapping cultural, economic, linguistic and political relationships. It can't be fully understood through a single interpretative tool, such as Class, and neither the members in it define themselves, at least most of the time, through a single dimension, such as religion. This means that there is no single lever to pull to bring social change about. This is not to claim that social change does not happen or shouldn't happen (more about this later) but this is usually a complex and longer-term enterprise than the revolutionaries would want us to believe.

Second, I believe that the economy is a social phenomenon and not a technical one. Because the phenomenon of the economy is usually seen through a limited set of perspectives (like GDP, Stock Market, price indices or per capita income) and understood to be driven by a set of powerful economic actors (the treasury, the bankers, the entrepreneurs or the trade unions), its ungovernable and deeper aspects are only visible periodically through crisis. In short, there is no single lever of the economy, visible or invisible. The reason why I think it's a deeply social phenomenon, rather than a distinct type (as in the Homo Economicus idealisation), is because it represents, at the aggregate level, our labours and our desires. We can be manipulated, by a vast symbolic-cultural system of money and education, to direct our labours and desires in a certain way for a certain time, but despite that, these remain inalienable from our social selves.

Third, I believe, after Simone Weil, that obligations precede rights, and even in an imaginary world where there may be no rights, there will always be obligations, at least to ourselves. Recognition of these obligations is central to our role in human society. Performance of these obligations is critical to the production and maintenance of that currency - trust - that makes the world function. The role of the individual, for me, is different from the acquisitive being imagined to be engaged in an endless pursuit of happiness; rather, a good life is defined by harmony, of recognising the obligations and of carrying them out, not as the solitary act of individual duty but within a vast network of interconnected human enterprise.

Fourth, I believe that while social change is inevitable, it's a continuous and dialectical process. Great men don't bring these about, nor cruel leaders stamp them out forever. On the other hand, there is no destination, nor a necessary direction, of social change. There will never be any heaven on earth, no perfect society, and there are no guarantees that tomorrow will be better than today. Change, instead, is natural, like from a day to another, and the aggregate of many little changes, some human but a vast amount of it lying beyond our capacity or comprehension. Our lives, lived around the performance of ritualised cycles, come bundled with an obligation to search for a better, kinder and harmonious future, without any promise that these could be ever attainable or any rewards. But it's that collective enterprise of living harmonious lives is at least as important as the millennia-long transformations of earth's surface temperature or the minutiae of its orbit around and tilt towards the Sun - and the two together shape the future for better or for the worse.

Finally, I believe that all progress comes from understanding, rather than creating ex nihilo. The journey of science is for me is a journey of understanding, of discovery, rather than creating new things altogether. No one makes a dent in my universe, but rather a few curious and humble few are, through pain-staking, generations-long exploration and engagement, gain a better understanding of the laws that govern us. This science is always provisional, a method rather than the fount of final answers. In this world, books balance, sooner or later.

Now, these ideas provide me with answers which will be close to a conservative's. For example, this makes me shun mortgages and overpriced houses, keeping in line with my childhood maxim of 'cut your coat according to your cloth'. It makes me suspicious of the Gurus who promise a better world, in this life or next. It makes me recognise that 'free markets' can not exist without a compassionate state, as without it, only the rights of few, and not the collective obligations, are really protected. It makes me see family as the starting point of responsible engagement with the world, but recognise the variety of human relationships can not be solely contained within it. It makes me recognise our obligations to nature and to take into account the full cost of our actions, present and in the future. This is not a world where progress is the objective but harmony is; it is not defined by a quest of happiness for self but rather for a greater understanding.

And, finally, I follow John Dewey's advice: Ideas should not become ideologies.

Should I not call myself a conservative?

Comments