Why liberalism is not the answer

I was protesting against cynical war-mongering by South Asian politicians on Facebook when a friend called me out: He blamed my 'liberal' ideology rather than my oft-expressed and admittedly utopian desire to see a peaceful and prosperous Asia for my ardour. I am used to be called socialist and even some cases, a communist, but 'liberal' is a first and that made me think.

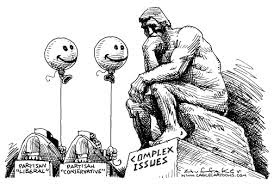

The popularity of the 'liberal' label is recent and bears a particular sense: An American one! It somewhat lumps a variety of things, socialism, free-markets and progressivism together for a start, without no other common theme than a belief that things would get better with time (which would have been called 'whiggism' at a different time). In that sense, liberalism should be seen opposed to the beliefs in a coming judgement-day that their opponents generally hold, though socialists, in that regard, should sit in the other side of the fence, in that sense.

But then, I am being too kind to myself: My friend didn't mean it to be a compliment! He used it in an even more contemporary sense: The new 'fascist'! I refer here to the description of fascism as 'something nasty, but you don't know what it is'. Liberal is, in the lexicon of Internet trolling, exactly that: Something wishy-washy, bad, though you can't say what it is!

Of course, there are people who love liberalism too, even in this day and age. The Economist gets almost teary-eyed about liberalism, invoking its grandees from Adam Smith to Tocqueville, and doing almost nostalgic opinion pieces. American think-tanks mourn the passing of the liberal world order, which roughly indicates the financial, military and ideological dominance of the United States, the post-war indirect imperialism model that was imposed on the world. They argue that something has gone seriously wrong and liberalism, being cast aside, has the remedy.

Unlike my description above, liberalism in this narrative has a very specific definition. It is an ideological position of nineteenth-century variety, built around secular polity, free market and individual rights. The ideas were positioned against the context of its time - the divinely ordained kings, mercantile empires and an ethic of life predetermined by the Church - and was couched in the beautiful language of Jefferson and Tocqueville and others.

Surely, Trump is no Louis Seizième and today's conservatives are really the radicals, but that gets completely missed in this conversation. Progressive ideas past their prime is an oxymoron, but we have stopped seeing it that way. And, The Economist and others conveniently omit that the nineteenth-century liberalism is a discredited narrative. Its formula of a global hegemonic power ended in unparallelled bloodshed in 1914; free-markets ended in tears in 1929; areligious celebration of individual freedom was overreached in '68; the carefully crafted structures of global finance was undone under its self-appointed high priests, Nixon and Volcker; and all the self-congratulatory neo-classical economics turned up to be a false God in 2008. It's only the nostalgia that is left, with a new scholastic urge to interpret foundational texts: The Liberal, as you will see, is the new Conservative.

That endeavour, though, is unlikely to provide any answers. One must remember context is everything here. Jefferson's invocation of inalienable rights was indeed poignant, but he was not compelled to mention its flip side - inescapable obligations and responsibilities - as his context made it all too obvious. The breaking of the power of the kings needed challenging the assumption that men - it was only men then, and white Christian men of West European descent - could self-govern themselves. The case for free markets rested in challenging the tangles of moral boundaries laid by the Church and governing powers. However, when those battles of legacy have been won though, the liberal canon is left with half-formed ideas: Democracy without education, markets without morals and rights without responsibility.

This is why I resent being called a Liberal. As its opponents very well know, Liberalism faces a crisis of credibility: Its politics is disconnected, its economics cruel and its morality is empty. Besides, it is not even practical anymore. The Liberal ascendancy in the nineteenth century went with expanding literacy and newspapers, a new consciousness of class, mass production and the emergence of common national identity. Without this environment, a common identity of individuality would be exactly as it sounds - absurd! Today's fragmented environment of media, personalisation, fashion and fetish, Liberalism only promises atomisation, the lonely road to selfishness. That sounds like the problem, rather than the solution.

That should not make me a pessimist though. It's common to commit to the fallacy that since believing in historical progress makes one liberal, a non-liberal wouldn't believe in progress. The Liberal-Millenarian dichotomy is a liberal invention, very European Christian and symptomatic of liberal narrow-mindedness. What I see this moment as one of a revolt of elites and the undermining of the nation-state by breaking the internal consensus that held them together, along with the final abandonment of the doctrine of sound money: A moment of liberal overreach rather than its redemption. What lies ahead, I believe, not cuddly politically correct mega-states and a global system of facebook democracy and google capitalism, but rather local economies and global democracies. I would rather be called an Utopian, but never a Liberal.

Comments