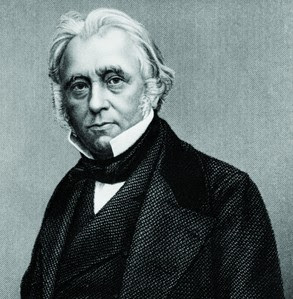

The Road to Macaulay: The Macaulay Moment

When he presented his Minutes in 1835, Macaulay’s mission was to align the educational funds, after its ten-fold increase, with the Utilitarian project of administrative and legal reforms. This was a break with the past, of all reverence towards any ‘ancient constitution’, but a reaffirmation of some continuities as well : The vision of a Military-Fiscal-Pedagogical state, a statement of moral confidence and recognition of a modernising mission. The Orientalist corpus of Indian antiquity supplied the idea of an antiquated India that needed to be transformed with European knowledge, just as Peter the Great effected on ancient Muscovy. The post-abolitionist confidence enabled Macaulay to transcend the fears of an reawakened Indian nation breaking off from the British, that constrained the thinking of earlier generations; rather, he celebrated such a possibility.

Macaulay’s arguments were based on appeal to pragmatic reason, and part of his own project of creating Codes of Law for India, which drew, in no small measure, from the Orientalist project of translating the Hindu and Muslim texts. He observed:

But this project had no sympathies with the Christianising mission that the evangelicals pursued for generations:

Macaulay’s conclusions were informed by the successes of colleges, mostly private and missionary colleges at this stage, in teaching English to Indians, which was no longer seen as an insurmountable problem:

However, in one crucial aspect, he remained committed to the continuity of earlier educational policy:

Macaulay’s intervention in Indian education was seen as a decisive shift from Orientalist to Anglicist policies, but this interpretation both obscures the lasting influence of Orientalism and policies such as ‘downward filtration’ and, crucially, the battles between the Secular and the theological ideas of education. Macaulay’s minutes and its consequences put an expansive state machinery in education, which would confront not only India’s traditional education system but also the Missionary enterprises that sought to offer a Christian education. This battle of ideas, which would play out in parallel with shifts within the liberal education ideals in Europe, would have a decisive role in shaping the idea of University of Calcutta.

Macaulay’s arguments were based on appeal to pragmatic reason, and part of his own project of creating Codes of Law for India, which drew, in no small measure, from the Orientalist project of translating the Hindu and Muslim texts. He observed:

The fact that the Hindoo law is to be learned from chiefly from Sanscrit books, and Mohammetan law from Arabic books, has been much insisted on but seems not to bear at all on the question. We are commanded by the Parliament to ascertain and digest the Laws of India. The Assistance of a Law Commission has been given to us for that purpose. As soon as the Code is promulgated the Shasters and the Hedaya will be useless to a Moonsiff or a Sudder Ameen. I hope and trust that, before the boys who are now entering at the Mudrassa and the Sanscrit College have completed their studies, this great work would be finished. It would be manifestly absurd to educate the rising generation with a view to a state of things which we mean to alter before they reach Manhood.

But this project had no sympathies with the Christianising mission that the evangelicals pursued for generations:

Assuredly it is the duty of the British government in India to be not only tolerant, but neutral on all religious questions… We abstain, and I trust shall always abstain, from giving any public encouragement to those who are engaged in the work of converting the natives to Christianity.

Macaulay’s conclusions were informed by the successes of colleges, mostly private and missionary colleges at this stage, in teaching English to Indians, which was no longer seen as an insurmountable problem:

I think it clear that we are not fettered by the Act of Parliament of 1813[;] that we are not fettered by any pledge expressed or implied[;] that we are free to employ our funds as we chuse; that we ought to employ them in teaching what is best worth knowing; that English is better worth knowing than Sanscrit and Arabic; that the natives are desirous to be taught `english, and are not desirous to be taught Sanscrit or Arabic[;] that neither as the language of law, nor as the language of religion, have Sanscrit and Arabic any peculiar claim to our encouragement; that it is possible to make natives of this country thoroughly good English scholars, and that to this end our efforts ought to be directed.

However, in one crucial aspect, he remained committed to the continuity of earlier educational policy:

In one point I fully agree with the Gentlemen to whose general views I am opposed. I feel with them that it is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions we govern[-]a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of this country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

Macaulay’s intervention in Indian education was seen as a decisive shift from Orientalist to Anglicist policies, but this interpretation both obscures the lasting influence of Orientalism and policies such as ‘downward filtration’ and, crucially, the battles between the Secular and the theological ideas of education. Macaulay’s minutes and its consequences put an expansive state machinery in education, which would confront not only India’s traditional education system but also the Missionary enterprises that sought to offer a Christian education. This battle of ideas, which would play out in parallel with shifts within the liberal education ideals in Europe, would have a decisive role in shaping the idea of University of Calcutta.

Comments