Many possible futures

Yesterday, I posted my thoughts on the Corona Virus pandemic and the pivot, or lack of it, that this may represent (see here). I was optimistic and concluded that while science will rise to the challenge, the shock will not break the economic system but instead reinvigorate it. But at the same time, a short crisis would indeed consolidate some of the worst aspects of our current social system - inequality, the surveillance state, national chauvinism - and leave us even worse off. The only hope I could see was in the resurrection of our political selves while the economic man has been forced into hibernation.

However, while I was far too certain, I was perhaps not clear enough. I considered only one kind of future, a rather short crisis, and yet, did not say what life on the other side of the crisis would really look like. While I am painfully aware that prediction is a perilous business, speculation in this season of uncertainty isn't out of place. But this, though, must start with the acknowledgement that at this fork of the road, we have many possible futures. But the multiplicity of the possibilities does not make an attempt to understand them futile; in fact, this enterprise is better than a hopeless surrender to despair.

Therefore, in this post, I have made explicit my various scenarios, each no more or less possible than the other; but all of them - as I see it - bide us to examine our ideas and assumptions regarding how we live our lives.

The Pandemic

Therefore, in this post, I have made explicit my various scenarios, each no more or less possible than the other; but all of them - as I see it - bide us to examine our ideas and assumptions regarding how we live our lives.

The Pandemic

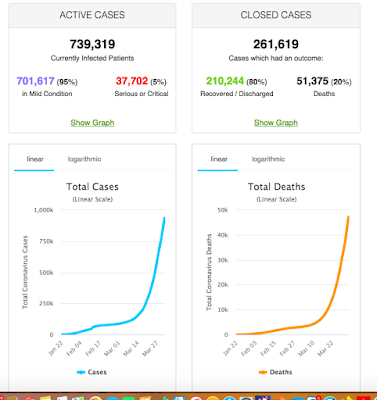

The starting point is that we don't know much about the Novel Corona Virus yet. We are still guessing its origin. We have some ideas about its transmission but still unsure about its gestation period. We have some sense of its mortality rates - that it's less fatal than Ebola but much more fatal than the common Flu - but we are still too early in the cycle to draw definite conclusions. We don't know exactly how many people have been infected and how long the infected people can continue to infect others. We have guessed that like the Common Flu and SARS before it, people will develop immunity once they have got the virus, but this hasn't been empirically proven yet. We have some candidate drugs for its treatment and may get something workable in the next few months, but a vaccine is possibly a couple of years away.

However, there are things we do know. Like China had effected a late but draconian lockdown on Wuhan and effectively controlled its spread. That the neighbouring countries, democracies all, acted early and with a combination of widespread testing and lockdown, slowed the spread of the epidemic and prevented a public health crisis. We know Germany has done relatively better, despite widespread infection, by testing widely. Also, we know how Italy faltered as it failed to protect its medical professionals and the UK lost nerve after initially dallying with a model to foster 'Herd Immunity'. UK's policy of centralising the testing - rather than going the 'Dunkirk route' of using all possible testing labs across the country - limited its capacity to test widely in the critical first days of the epidemic. And, we also know the 'virus deniers' in the US - and possibly in Brazil and India after them - may make their countries pay a terrible price.

The road ahead, therefore, is clear. Mass testing and quarantine where and when necessary will help us conquer the pandemic. Denial and open-market callousness will make things worse and the crisis long-drawn. With our current level of knowledge of genes and viruses, we will find a makeshift cure within the next few months and a vaccine, perhaps by Autumn 2021. However, the current experience points to an important lesson: That evasion, data fudge and variability of responses are responsible for making the crisis as bad as it is today. And, indeed, even if a country has managed its affairs, it will be impossible to return to normalcy without a coordinated international response. So, though it is much maligned, the hopes of putting Corona Virus behind us rest on the effective functioning of international institutions, not just of WHO but also of United Nations prodding the nations into a coordinated policy response. Whether that can be done will determine whether this is going to be a long or a short pandemic: Dragging along until the Autumn 2021 through several waves or getting to a containment and normalisation stage by Autumn 2020. If we walk the road that we have taken so far, we are in for a long crisis; but then one hopes that the economic costs may tip the governments over to the other direction.

The Geopolitics

The other question is whether this marks the end of America's global leadership and the beginning of a Chinese-dominated future. No doubt America has failed to provide leadership and instead set quite a bad example with denial and mismanagement of the crisis. But China has faltered too - it behaved extremely irresponsibly in the initial period of the spread - and it will not be easily forgiven for that. In fact, the crisis exposed a faultline. We wouldn't exaggerate much in comparing this with the interwar years when Britain was unwilling or unable to provide global leadership and America was still not ready. It seems that China still lacks the will or confidence to take the responsibilities that come with pre-eminence while America, under the burden of over-extension of its military commitments, is retrenching.

What happens next will be determined by the length of the crisis. A short crisis would need a return to the international institutional framework, the only way to reassert American leadership. But since there is a real chance that this American leadership will not return to internationalism because of ideological reasons (and for idiosyncrasies of the US President), there is a risk of this crisis dragging on longer than it should. China has been pragmatic so far - it had projected a benevolent attitude towards Europe and poorer nations - but its actions would be, justifiably, seen more as an admission of guilt instead of leadership. And, in the absence of leadership, the geopolitics is in the same slippery territory it was a hundred years ago. A long crisis, if it comes, would mean the current authoritarian governments would become even more authoritarian, which, in turn, would encourage more authoritarianism in other countries. We may have been there before in history and it's a very bad place to be.

The economy

Locked in so the economy has broken down. There is no question about that. The question is whether we are going to have the 'great depression' as some people are predicting.

The key here is in the expectations. Right now, most of the people are expecting a long-drawn-out period of inactivity. In fact, there is a real possibility that this can go on well until the end of the year, and even if the lockdown is relaxed before that, international travel and exchange are unlikely to be resumed until all countries can be certified free of the virus. Despite some of the governments announcing big stimulus, the banks and other financial institutions are still circumspect.

Therefore, anything shorter will actually provide a bounce in economic activity. This is what I am expecting. Not that the fear of infection will go away - and therefore, it would still bring about changes in working practices in different sectors - but the confidence in the ability of public healthcare to cope with it and in the prospect of recovery, which is somewhat low right now, would bring about a change in investor sentiments. Such a crisis would be like the Second World War, which, despite the death and destruction, led to a quick economic recovery afterwards.

The politics

Usually, a crisis is good for the government, as it allows the opportunity to show that it's doing something. Modern governments are very very powerful and times like this remove the restraints they operate within (such as civil rights or limits of public expenditure). It is astounding what the governments can really do - who would have thought a Tory government can guarantee business loans - and that is likely to strengthen the governments and the megalomaniacs that run them in some countries, for now.

But this depends on the length of the crisis. If it runs for too long, the chinks in the armour will show. Because, despite the vast power, the commitment to service is not the public servants' forte anymore. Besides, a crisis is also good for various forms of profiteering interests and they would try to corner as much of the upside as they can, often at the cost of the much-needed welfare. Corruption will spread and over time, become visible. As much a short crisis helps the governments, a long one will allow everyone to show their incompetence - and erode its credibility.

So a long crisis can lead to political crisis and in some fragile cases (such as Britain) lead to state break-ups. On the other hand, a shorter one may give us Trumps-on-steroid.

Bottom Line

In conclusion, then, the outcomes may be very different based on the length of the crisis. Resumption of economic activity by the end of April or middle of May would count as a short crisis, something stretching beyond summer would be a long one.

During this time, public policy will become one of choice between different trade-offs of potential infection and mortality and economic damage, arrayed as what the economists will call an 'Indifference Curve' (without irony: Economics don't do irony). Any quick resolution of the threat would require some kind of global consensus on the point on this Indifference Curve we should be aiming for. That wouldn't happen without imagination and leadership, the two things which have been in short supply so far.

Other than that, we should pray for miracles. Such as, this Virus can't survive in warm weathers. And, once you get it, you will develop immunity - and such immunity will last at least a year. And, one of the candidate drugs may indeed provide a cure. That the regions with a long history of Malaria may be better resistant to the spread of the Virus. BCG vaccination may work against the virus - a huge pay-off on all the public health investments since after the war.

Comments